Buckle up as this will be a lengthy one. There will be design decisions that you might not agree with and that is okay. It was not my intention initially to write such a long post but it turns out talking about controversial topics might take a few extra words. You can use the table of content to help navigating quickly betweens sections. There are three parts to the “Styling Svelte Vietnam” blog series, listed below. You are reading the first one.

This post is also part of the “Behind the Screen” series, where I share my experience and lessons learned while building sveltevietnam.dev. You can find the pervious post at ”Progressive Splash Screen“.

Let us begin.

The TailwindCSS Debate

Tailwind has become a trending keyword and hot topic that can easily spark disagreement from different points of view. Some love it and will spend significant effort making sure you hear what they have to say. Others hate it and will affirm that Tailwind is bad and needs to be shooed away at all costs. Try searching for “Tailwind love and hate” on Google or Twitter and you will be greeted with such heated conversations. In a few words, people love Tailwind for its flexibility, development speed, and integration with existing ecosystem; people hate Tailwind for its arguably bloated CSS output and degraded readability due to the heavy use of utility classes in markup.

Here is my argument when asked about this: the “Tailwind idea” is not new! Using .mx-4 instead of the otherwise explicit margin-left: 16px; margin-right: 16px has been a common practice for more than a decade in CSS libraries, namely Bootstrap. If you have worked in a project with relatively complex design system, chances are you have already encountered or even set up yourself similar abstractions.

The most distinguishable differences between Tailwind and previous solutions are:

- a focus on utility classes - providing minimal abstractions that map intuitively to corresponding CSS - instead of UI components. For example, Tailwind will stop at

.ml-4instead of.accordionor.btn-primary. - building upon PostCSS, providing a powerful API for customization, and rich editor support via its language server.

For me, Tailwind is a great tool, and when used correctly can help boost productivity without trading off code quality and maintainability.

Tailwind for Quick Prototyping

When building an MVP or testing ideas, a key priority is speed. Tailwind is a fitting solution for this phase as it effectively allows co-locating styles right next to markup, making it easy to set up, search, and change. Instead of spending time designing a complex project structure or coming up with a convoluted naming convention like BEM…

<!-- BEM markup & styling -->

<prototype>

<block class="block">

<element class="block__element block__element--modifer">

this will definitely be refactored later

</element>

</block>

</prototype>

<style lang="postcss">

.block {

& .block__element {

&.block__element--modifier {

/* prototype styling */

}

}

}

</style>…why not use Tailwind’s built-in classes that most developers are already familiar or can easily get up to speed with:

<!-- Tailwind -->

<prototype>

<block class="flex items-center mx-auto">

<element class="py-4">

this will definitely be refactored

</element>

</block>

</prototype>A project with beautiful code, fancy structure, and strict conventions but no users is not that useful, is it? Instead of debating how to name blocks and elements, or where to find the corresponding CSS for certain markup, we can save time and focus on making the actual product. This does not mean, however, that we write code recklessly: Tailwind is such a simple abstraction layer that we can easily refactor or scale up, especially when design patterns and UI requirements has come to light as the project grows.

Tailwind for Creating Design System

As the project matures, there comes a time when we need to think about design system (color palette, typography, spacing, …). This is where Tailwind really shines: it allows customizable configuration for almost every aspect of the library. In the following example, we define the “Inter” font and a primary color:

/** @type {import('tailwindcss').Config} */

export default {

content: ['./src/**/*.{html,js,svelte,ts,md}', 'svelte.config.js'],

theme: {

extend: {

fontFamily: {

inter: ['Inter', 'sans-serif'],

},

colors: {

primary: 'hsl(10 100% 54%)',

},

},

},

};These “design tokens” are defined in Javascript, giving us the liberty of doing anything we wish as long as Javascript allows it: map, filter, transform colors, utilize API from Tailwind or other libraries, … By specifying the above configuration, we are already granted three access points:

using the generated classes directly in the markup, for example:

<element class="font-inter text-primary"></element>accessing design tokens in CSS via the theme(…) function, for example:

.element { font-family: theme('fontFamily.inter'); color: theme('colors.primary'); }accessing from Javascript. For example, we can have all colors defined in a separate file and import where necessary. This is exactly how sveltevietnam.dev structure its color palette; you can read our source code here.

// colors.js export const colors = { primary: 'hsl(10 100% 54%)', // ... };

Projects using Tailwind that I have been a part of all needed custom configuration to some extent, similar to the above example, to satisfy design requirements and coding convention. If you have worked in systems at scale using other CSS management and packaging solutions, namely Sass, I assume you would agree that building a design system is a huge time-consuming undertaking. To achieve comparable complexity and flexibility to those of Tailwind, you must have had many years of experience or perhaps even built your own tooling or framework! Lately, there have been many UI solutions that either integrate with or recommend Tailwind: daisyUI, Flowbite, Skeleton, shadcn/ui to name a few.

Don’t serve Tailwind. Let Tailwind serve you

Let’s talk a bit about the argument that Tailwind “forces” us to add too many classes to markup, causing poor readability or maintainability; or that Tailwind makes people no longer able to write CSS. I personally think in these scenarios, we are unknowingly serving Tailwind: we think of it as a framework and its approach is sole. We should, on the contrary, view Tailwind just as a tool in a rich CSS ecosystem. Instead of only using Tailwind all the time, just do when necessary; write CSS as needed, use PostCSS on demand!

Don’t teach or learn CSS via Tailwind: that is a risky path. If you are getting started with CSS, learn the traditional, vanilla CSS. When finding solution for a practical problem, we should not start with “how do I do this in Tailwind?” but rather “what can I do in CSS?”, only after which should we look into whether Tailwind provides the right abstraction for the job.

For example, instead of putting everything in the markup…

<form class="py-4">

<p>...</p>

<button class="mt-4 px-4 py-2 text-center font-semibold rounded-md bg-white hover:bg-black hover:text-white">

Button

</button>

</form>…we can use Tailwind to access design tokens within CSS and extract complex patterns…

@layer components {

.c-btn {

padding: theme('spacing.2') theme('spacing.4');

text-align: center;

font-weight: theme('fontWeight.semibold');

border-radius: theme('borderRadius.md');

background-color: theme('colors.white');

&:hover {

background-color: theme('colors.black');

color: theme('colors.white');

}

}

}…and only use Tailwind classes for inter-relational spacing and alignment between elements:

<button class="mt-4 px-4 py-2 text-center font-semibold rounded-md bg-white hover:bg-black hover:text-white">

<button class="mt-4 c-btn">

Button

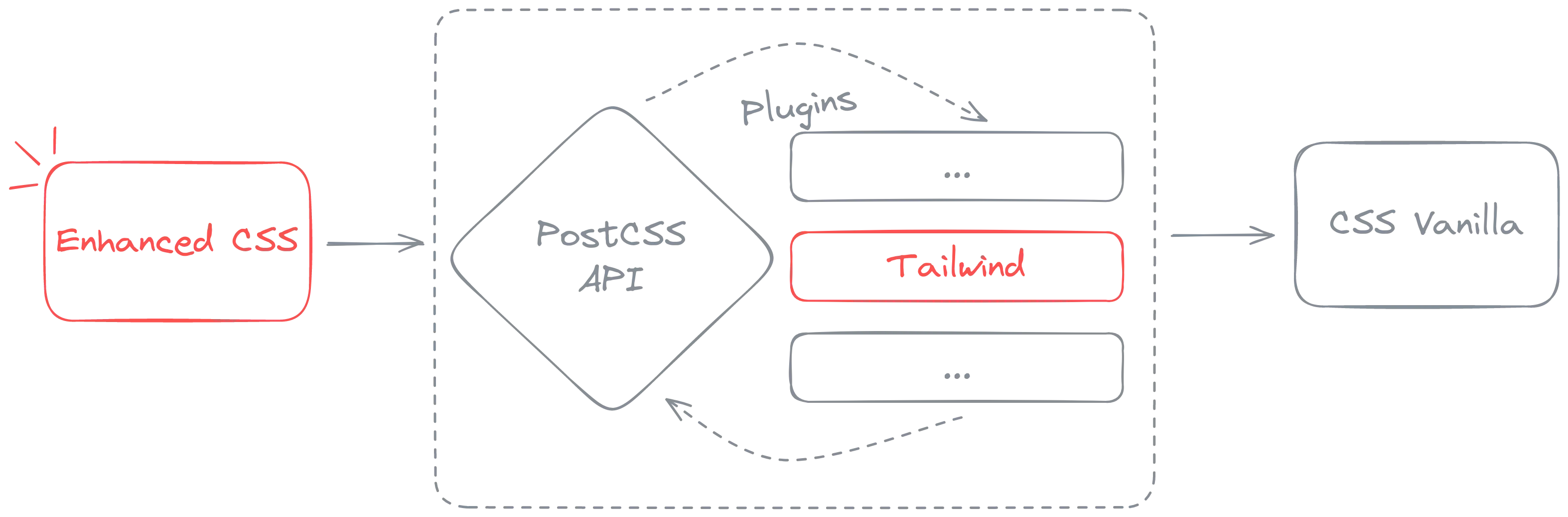

</button>Tailwind with PostCSS

To a certain extent, we can view Tailwind simply as a PostCSS plugin. This means we can use Tailwind in conjunction with other PostCSS plugins, and, vice versa, use PostCSS API to extend Tailwind configuration.

In the post ”Productive Dark Mode with SvelteKit, PostCSS, and TailwindCSS”, I have introduced two special syntaxes in support for implementing dark mode. The first extends CSS:

p {

@dark {

color: white;

}

}The second extends Tailwind and is used in markup:

<p class="dark:text-white">...</p>The two syntax above are equivalent in output. Both come from the same PostCSS plugin postcss-color-scheme, which I wrote. Thanks to the compatibility of Tailwind with PostCSS, we can provide two solutions for developers to utilize depending on specific each use case. And if I could write such plugin, I can assure that you can do similar, even greater things!

Tailwind in Svelte

The Tailwind documentation site provides instruction for setup and usage in SvelteKit. Using Tailwind in Svelte is not that different from using it in other frameworks; techniques introduced in this series are all applicable. However, you should be cautious when using @apply. This syntax inlines actual CSS in place of specified utility classes. Let’s look at the following, for example:

/* input.css */

.btn {

@apply font-bold py-2 rounded;

padding-inline: 16px;

}The output will be:

/* output.css */

.btn {

font-weight: 800;

padding-top: 8px;

padding-bottom: 8px;

border-radius: 0.25rem;

padding-inline: 16px;

}In general, I do not recommend using @apply. As you can see from the example above, this feature is quite convenient. However, it mixes two different syntaxes, bringing HTML classes into CSS. If abused, this approach will create technical debt that hinders maintenance and optimization. We often use @apply to extract reusable CSS, but this can also be done by extending Tailwind configuration, which we will discuss deeper in the later parts of this series.

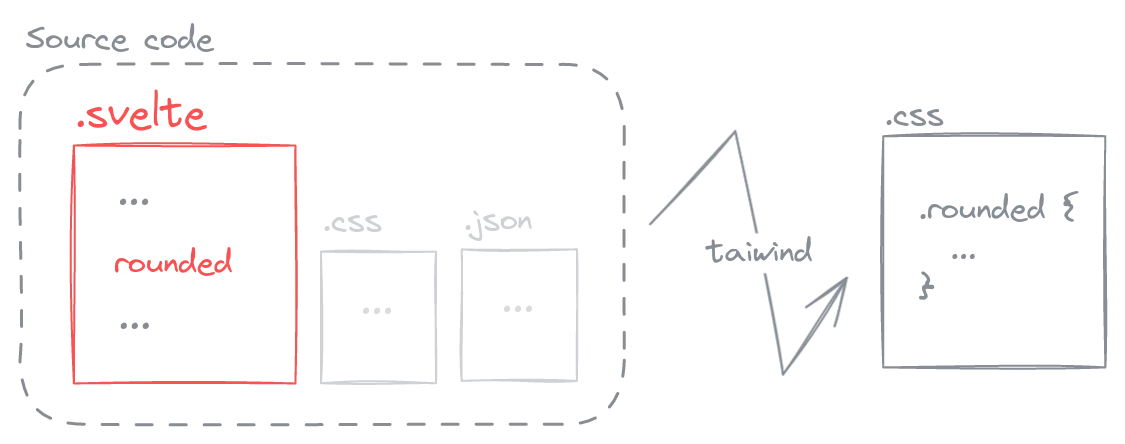

Besides, using @apply in *.svelte files should be avoided for two reasons. One is the fact that it may not work as one might expect, as discussed here in the Tailwind documentation. Secondly, the build output might be polluted with unused classes. To understand this, let’s have an overview of how Tailwind works.

/** @type {import('tailwindcss').Config} */

export default {

content: ['./src/**/*.{html,js,svelte,ts}'],

};Tailwind’s configuration contains a mandatory content field, which instructs the Tailwind just-in-time compiler where in source code to read and search for applicable class names (mx-auto, pl-2, rounded, …) and output corresponding CSS. Say we have the following Svelte file:

<article>...</article>

<style lang="postcss">

article {

@apply rounded;

}

</style>The output of the whole process (SvelteKit + Tailwind) looks something like this:

/* example.css */

article.svelte-hash {

border-radius: 0.25rem;

}

.rounded {

border-radius: 0.25rem;

}

Notice the highlighted lines in yellow: they are not needed. We do not use the rounded class anywhere in the markup, but since “rounded” is a matching keyword in example.svelte, which is included in the content configuration`, Tailwind thinks it is necessary in the output.

In situations where output size optimization is required, understanding this will be greatly beneficial. When using daisyUI, for example, its class names use common keywords such as card, dropdown, table. As long as your source code contains these keywords, the corresponding CSS will be included in the output, whether you actually use it or not. That is why Tailwind and daisyUI provide prefix configuration, which helps transform keywords to less ambiguous ones, for example daisy-card, daisy-dropdown, daisy-table, …

In short, avoid using @apply, and if necessary, only do so in *.css files to avoid complex setup or pollution in build output.

Closing

In conclusion, I have no reason to hate Tailwind as a tool with such flexibility and productivity boost. The reasoning in this post is the foundation upon which sveltevietnam.dev builds its design system and structure CSS. We will discuss this in more detail in the next two parts of the “Styling Svelte Vietnam” series.

Join the Svelte Vietnam Discord for more discussion, or read the next part at ”Styling Svelte Vietnam: Part II - CSS Component”. Thank you very much for reading!

Found a typo or need correction? Edit this page on Github